Natalie BIRECKI

Amulettes comestibles

Natalie BIRECKI (Saguenay)

Exposition, Terminé(e)

Du 23 octobre 2025 au 4 janvier 2026

Salle projet, Salle vidéo

Vernisage le 23 octobre 2025, 17:00

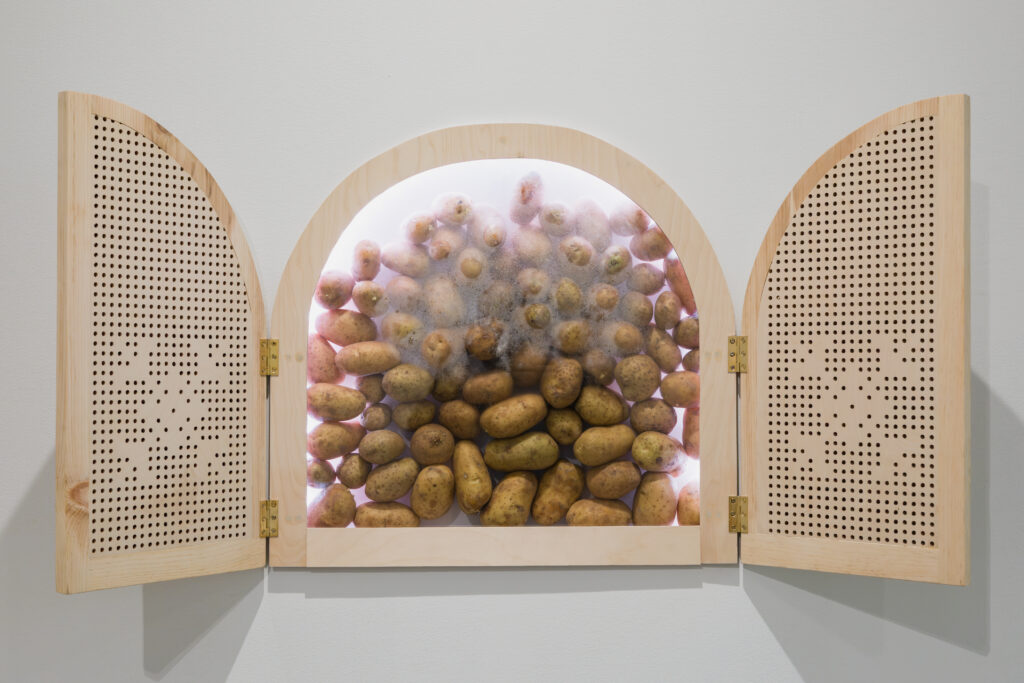

ENG and POL will follow

Amulettes comestibles explore l’émergence d’une « troisième culture » née de la rencontre entre l’héritage polonais de l’artiste et son ancrage québécois. Plutôt qu’une simple juxtaposition identitaire, cette cohabitation agit comme un espace de transformation où les traditions se réinventent au contact du quotidien. Chez Birecki, la cuisine devient un lieu de métamorphose symbolique : les objets frits, à la fois profanes et sacrés, sont un moyen d’incarner des valeurs, de transmettre des histoires, d’inscrire une mémoire dans le corps. Amulettes comestibles propose ainsi une table d’offrandes contemporaines où se conjuguent mémoire, humour et tendresse – un laboratoire intime où le foyer devient atelier et la maternité, un acte de création.

L’ARTISTE

Natalie Birecki vit et travaille au Saguenay, où elle tisse des liens entre matière, imaginaire et territoire. Diplômée de l’Université du Québec à Chicoutimi (2016), elle explore les porosités entre art, artisanat et quotidien. Ses résidences, dont la dernière fut réalisée avec Langage Plus dans son programme ArAMiS (2025), nourrissent une pratique ancrée dans la lenteur et la métamorphose. En 2017, elle fonde Vagabondes, collectif de micro-édition né d’une résidence sur l’île d’Anticosti. Artiste-pédagogue, Birecki cultive une pratique habitée par la tendresse du geste, la mémoire des objets et la poésie des formes familières.

Un mot de l’artiste (texte de Natalie BIRECKI)

Ma pratique artistique prend racine principalement dans la céramique, un médium qui exige patience, répétition et transformation. Façonner l’argile, la cuire, la rendre durable est un processus qui, depuis longtemps, m’apparaît comme une métaphore de la vie domestique. C’est dans la cuisine, lieu quotidien et intime, que cette métaphore se prolonge. Là, les ingrédients subissent eux aussi des métamorphoses: ils sont pétris, cuits, transformés par le feu ou l’huile, avant d’être partagés. Dans les deux cas – céramique et cuisine – la matière brute devient vecteur de mémoire et de récit.

La maternité et la vie familiale traversent naturellement mon travail. La cuisine, souvent associée à la sphère féminine et aux soins du quotidien, devient mon premier atelier: un lieu d’exploration où se rencontrent les impératifs du foyer et l’imaginaire artistique. Préparer un repas pour un enfant, répéter les mêmes gestes jour après jour, observer comment les objets circulent et se transforment – ces expériences banales deviennent des points d’ancrage pour une réflexion plus vaste sur la transmission culturelle et le sens des rituels.

Dans Amulettes comestibles, les objets et les symboles se situent à la croisée de plusieurs héritages. On y retrouve des références polonaises, comme la galaretka, archive comestible où se suspendent récits et mémoires contemporaines, ou les motifs traditionnels de Bolesławiec qui se déploient sur une tour de contenants à emporter, objets du jetable, devenant ainsi porteurs de continuité et de permanence. Ce n’est pas simplement une juxtaposition de traditions: c’est un espace où elles se confrontent, se déplacent et se réinventent.

Plutôt que de figer les traditions dans une nostalgie statique, mon travail interroge leur circulation, leur transformation et leur réinvention dans un contexte diasporique. L’hybridité culturelle que j’explore ne naît pas d’un simple mélange, mais d’une tension féconde: entre l’héritage polonais, transmis par l’expérience familiale, et l’ancrage québécois qui façonne mon quotidien.

Plutôt qu’un simple mélange de traditions, le projet s’intéresse à l’hybridité culturelle comme à un lieu intermédiaire où surgit une « troisième culture ». Ni totalement héritée, ni totalement acquise, cette culture hybride est un espace de friction, de jeu et de réinvention. Elle prend racine dans l’héritage de l’immigration parentale, dans une vie familiale traversée par plusieurs appartenances, et dans la nécessité de traduire au quotidien deux univers culturels en un seul langage sensible.

Cette troisième culture est fragile, mais fertile. Elle ne se contente pas de juxtaposer des symboles: elle les transforme. Dans mon travail, elle se matérialise par la friture d’objets qui incarnent une forme d’ambivalence: à la fois reliques et objets de consommation, elles oscillent entre l’objet sacré et la gourmandise profane. Le geste de les plonger dans l’huile n’est pas un blasphème, mais une manière de réinscrire le sacré dans le quotidien. Comme l’huile qui oint et transforme, la friture opère une métamorphose: elle renverse l’autorité du sacré tout en lui conférant une nouvelle aura. Par l’humour et la tendresse, ces objets religieux domestiqués réinventent le rapport au religieux, en l’ouvrant à l’espace intime de la famille et de la table.

La troisième culture n’est ni un compromis, ni une perte d’authenticité: c’est un espace de création. Elle révèle ce qui se joue entre deux mondes, là où les identités se négocient et se redéfinissent. C’est une culture mouvante, ouverte, qui refuse la clôture et la pureté. Comme la céramique et comme la cuisine, elle est faite de gestes de soin, de patience et de feu. Elle exige une pratique constante de réinvention, où chaque objet, chaque aliment, chaque rituel devient une amulette capable de protéger, de questionner et de transmettre.

La nourriture agit alors comme un véhicule de cette hybridité. Comme la religion, elle repose sur des rituels répétés et collectifs: préparer un repas, célébrer une fête, partager une table. Elle est un moyen d’incarner des valeurs, de transmettre des histoires, d’inscrire une mémoire dans le corps. C’est pourquoi certaines œuvres de l’exposition mettent en lumière la proximité entre croyance et alimentation. L’une comme l’autre transforme la matière en symbole, et fabrique du lien.

Amulettes comestibles devient ainsi une table d’offrandes contemporaines, un espace où l’ordinaire – ustensiles, gelées, contenants, nourriture – se charge de magie. C’est une invitation à considérer le foyer comme un laboratoire culturel, la cuisine comme un atelier, et la maternité comme un geste artistique en soi. Au cœur de cette démarche, une conviction: ce qui se transmet, par la nourriture comme par les objets, ne se limite pas à une tradition figée, mais ouvre à l’émergence d’une troisième culture, mouvante, fragile, mais profondément créatrice.

DÉMARCHE ARTISTIQUE

La pratique de Natalie Birecki explore la cohabitation entre les objets et les individus, révélant l’ironie et la poésie de cette symbiose. Par l’assemblage de matières contrastées et d’objets du quotidien, elle crée des sculptures hybrides où s’entrelacent artisanat, culture populaire et iconographie religieuse. Cette alchimie des formes et des symboles devient un terrain de tension entre la tradition et la modernité, entre l’utile et l’inutile. L’artiste s’intéresse particulièrement à la domesticité et au rôle de la mère-artiste, investissant la sphère intime comme un espace de création et de réflexion.

En assumant une esthétique kitsch empreinte de folklore, Birecki transforme le banal en merveilleux, le familier en sacré. Son œuvre, à la fois ludique et critique, interroge les constructions sociales et les héritages culturels tout en ouvrant un espace d’ambiguïté fertile — un monde où la matière, le geste et le hasard s’unissent pour réenchanter le réel.

Capsule DÉCODEUR

Réalisée en 2025 par Jean-François Bourbeau, cette capsule est le fruit d’une collaboration avec Eckinox.

ENG version

Edible amulets

Edible Amulets delves into the emergence of a “third culture” born from the convergence of the artist’s Polish heritage and her rootedness in Quebec. Rather than a mere juxtaposition of identities, this coexistence becomes a transformative space where traditions are reimagined through the lens of the everyday. In Birecki’s practice, the kitchen is elevated to a site of symbolic metamorphosis: fried objects— both sacred and profane — serve as vessels for embodying values, transmitting stories, and inscribing memory into the body. Edible Amulets thus unfolds as a contemporary offering table where memory, humor, and tenderness intertwine—an intimate laboratory in which the domestic sphere becomes a studio, and motherhood, an act of creation.

Edible amulets

My artistic practice is rooted primarily in ceramics, a medium that demands patience, repetition, and transformation. Shaping clay, firing it, and making it durable has long seemed to me a metaphor for domestic life. This metaphor extends into the kitchen, a daily and intimate space. There, ingredients undergo transformations as well: they are kneaded, cooked, altered by fire or oil, before being shared. In both cases—ceramics and cooking—raw materials become carriers of memory and narrative. Motherhood and family life naturally permeate my work. The kitchen, often associated with the feminine sphere and everyday care, becomes my first studio: a space of exploration where the imperatives of home intersect with artistic imagination. Preparing a meal for a child, repeating the same gestures day after day, observing how objects move and change—these mundane experiences become anchor points for a broader reflection on cultural transmission and the meaning of rituals.

In Edible Amulets, objects and symbols sit at the crossroads of multiple heritages. References to Poland appear, such as galaretka, an edible archive where contemporary stories and memories are suspended, or traditional Bolesławiec patterns that unfold on a tower of takeout containers — disposable objects that thus carry continuity and permanence. It is not simply a juxtaposition of traditions; it is a space where they confront, shift, and reinvent themselves. Rather than freezing traditions in static nostalgia, my work interrogates their circulation, transformation, and reinvention within a diasporic context. The cultural hybridity I explore does not arise from mere mixing, but from a fertile tension: between the Polish heritage transmitted through family experience and the Québécois grounding that shapes my daily life. Rather than a simple mixture of traditions, the project investigates cultural hybridity as an intermediate space where a “third culture” emerges. Neither fully inherited nor entirely acquired, this hybrid culture is a space of friction, play, and reinvention. It takes root in the inheritance of parental immigration, in a family life traversed by multiple affiliations, and in the necessity of translating two cultural worlds into a single sensitive language.

This third culture is fragile but fertile. It does not merely juxtapose symbols: it transforms them. In my work, it materializes through the frying of objects that embody a form of ambivalence: both relics and consumables, they oscillate between the sacred object and profane indulgence. Immersing them in oil is not blasphemy, but a way of reinscribing the sacred into daily life. Like the oil that anoints and transforms, frying effects a metamorphosis: it overturns the authority of the sacred while granting it a new aura. Through humor and tenderness, these domesticated religious objects reinvent the relationship to the sacred, opening it to the intimate space of family and the table.

The third culture is neither a compromise nor a loss of authenticity: it is a space of creation. It reveals what happens between two worlds, where identities are negotiated and redefined. It is a fluid, open culture that rejects closure and purity. Like ceramics and cooking, it is built through gestures of care, patience, and fire. It demands a constant practice of reinvention, where each object, each food, each ritual becomes an amulet capable of protecting, questioning, and transmitting.

Food thus acts as a vehicle for this hybridity. Like religion, it relies on repeated and collective rituals: preparing a meal, celebrating a festival, sharing a table. It embodies values, transmits stories, and inscribes memory in the body. That is why some works in the exhibition highlight the proximity between belief and nourishment. Both transform matter into symbols and create bonds.

Edible Amulets becomes, in this sense, a table of contemporary offerings, a space where the ordinary—utensils, jellies, containers, food—is charged with magic. It is an invitation to consider the home as a cultural laboratory, the kitchen as a studio, and motherhood as an artistic gesture in itself. At the heart of this approach lies a conviction: what is transmitted, through food as through objects, is not limited to a fixed tradition, but opens the way to the emergence of a third culture—fluid, fragile, but profoundly creative.

THE ARTIST

Natalie Birecki lives and works in Saguenay, where she weaves connections between material, imagination, and territory. A graduate of the Université du Québec à Chicoutimi (2016), she explores the porous boundaries between art, craft and daily life. Her residencies, including the most recent one with Langage Plus through its ArAMiS program (2025), nurture a practice rooted in slowness and transformation. In 2017, she founded Vagabondes, a micro-publishing collective born from a residency on Anticosti Island. As an artist-educator, Birecki cultivates a practice animated by the tenderness of gesture, the memory of objects, and the poetry of familiar forms.

ARTISTIC APPROACH

Natalie Birecki’s practice explores the coexistence between objects and individuals, revealing the irony and poetry embedded in this symbiosis. Through the assemblage of contrasting materials and everyday objects, she creates hybrid sculptures where craft, popular culture, and religious iconography intertwine. This alchemy of forms and symbols becomes a field of tension between tradition and modernity, between the useful and the useless.

Deeply interested in domesticity and the role of the artist-mother, Birecki invests the intimate sphere as a space of creation and reflection. Embracing a kitsch aesthetic infused with folklore, she transforms the banal into the marvelous, and the familiar into the sacred. Her work,both playful and critical, questions social constructs and cultural inheritances while opening a fertile space of ambiguity: a world where matter, gesture, and chance come together to re-enchant the real.

POL version

Jadalne Amulety

Moja praktyka artystyczna zakorzeniona jest przede wszystkim w ceramice, medium wymagającym cierpliwości, powtarzalności i przemiany. Formowanie gliny, jej wypalanie i nadawanie trwałości od dawna jawi mi się jako metafora życia domowego. Ta metafora przedłuża się w kuchni, codziennej i intymnej przestrzeni. Tam r.wnież składniki przechodzą przemiany: są wyrabiane, gotowane, zmieniane przez ogień lub olej, zanim zostaną podzielone. W obu przypadkach—ceramice i gotowaniu—surowiec staje się nośnikiem pamięci i opowieści. Macierzyństwo i życie rodzinne naturalnie przenikają moją tw.rczość. Kuchnia, często kojarzona z kobiecą sferą i codzienną troską, staje się moim pierwszym atelier: przestrzenią eksploracji, w kt.rej spotykają się domowe obowiązki i wyobraźnia artystyczna. Przygotowywanie posiłku dla dziecka, powtarzanie tych samych gest.w dzień po dniu, obserwowanie, jak przedmioty krążą i się zmieniają—te zwyczajne doświadczenia stają się punktami oparcia dla szerszej refleksji nad przekazywaniem kultury i znaczeniem rytuał.w. W Jadalnych Amuletach przedmioty i symbole znajdują się na skrzyżowaniu wielu dziedzictw. Pojawiają się odniesienia do Polski, takie jak galaretka, jadalne archiwum, w kt.rym zawieszone są wsp.łczesne opowieści i wspomnienia, lub tradycyjne wzory z Bolesławca, rozwijające się na wieży pojemnik.w na wynos—jednorazowych przedmiotach, kt.re tym samym stają sięnośnikami ciągłości i trwałości. Nie jest to po prostu zestawienie tradycji; to przestrzeń, w kt.rej one się konfrontują, przesuwają i na nowo tworzą. Zamiast utrwalać tradycje w statycznej nostalgii, moja praca bada ich krążenie, przemianę i reinwencję w kontekście diaspory. Hybrydyczność kulturowa, kt.rą eksploruję, nie wynika z prostego mieszania, lecz z tw.rczego napięcia: między polskim dziedzictwem przekazywanym przez doświadczenie rodzinne a kwestionowalnym zakorzenieniem w codziennym życiu w Quebecu.

Projekt bada hybrydyczność kulturową jako przestrzeń pośrednią, w kt.rej rodzi się „trzecia kultura”. Nie w pełni odziedziczona, ani całkowicie nabyta, ta hybrydowa kultura jest przestrzenią tarcia, gry i reinwencji. Korzenie bierze z dziedzictwa migracji rodzic.w, życia rodzinnego przenikanego przez r.żne przynależności oraz konieczności codziennego tłumaczenia dw.ch świat.w kulturowych na jeden wrażliwy język. Ta trzecia kultura jest krucha, lecz płodna. Nie ogranicza się do zestawiania symboli: ona je przemienia. W mojej pracy materializuje się poprzez smażenie przedmiot.w, kt.re uosabiają ambiwalencję: zar.wno relikwie, jak i przedmioty konsumpcyjne, oscylujące między obiektem świętym a profanacją. Zanurzenie ich w oleju nie jest bluźnierstwem, lecz sposobem na ponowne wpisanie sacrum w codzienność. Jak olej, kt.ry namaszcza i przemienia, smażenie dokonuje metamorfozy: przewraca władzę sacrum, jednocześnie nadając mu nową aurę. Poprzez humor i czułość, te udomowione przedmioty religijne reinventują relację z sacrum, otwierając ją na intymną przestrzeń rodziny i stołu. Trzecia kultura nie jest kompromisem ani utratą autentyczności: jest przestrzenią tw.rczości. Ukazuje, co dzieje się między dwoma światami, gdzie tożsamości są negocjowane i redefiniowane. Jest kulturą płynną, otwartą, odrzucającą zamknięcie i czystość. Jak ceramika i gotowanie, opiera się na gestach troski, cierpliwości i ognia. Wymaga stałej praktyki reinwencji, gdzie każdy przedmiot, każdy pokarm, każdy rytuał staje się amuletem zdolnym chronić, pytać i przekazywać.

Jedzenie staje się więc nośnikiem tej hybrydyczności. Jak religia, opiera się na powtarzalnych i zbiorowych rytuałach: przygotowywanie posiłku, celebrowanie święta, dzielenie się stołem. Uosabia wartości, przekazuje historie, zapisuje pamięć w ciele. Dlatego niekt.re prace w wystawie uwypuklają bliskość między wiarą a pożywieniem. Oba przekształcają materię w symbol i tworzą więzi.

Jadalne Amulety stają się w ten spos.b stołem wsp.łczesnych ofiar, przestrzenią, w kt.rej zwyczajne—narzędzia, galaretki, pojemniki, jedzenie—nabiera magii. To zaproszenie, by uznać dom za laboratorium kulturowe, kuchnię za atelier, a macierzyństwo za gest artystyczny sam w sobie. W centrum tego podejścia leży przekonanie: to, co jest przekazywane, poprzez jedzenie czy przedmioty, nie ogranicza się do utrwalonej tradycji, lecz otwiera drogę do powstania trzeciej kultury—płynnej, kruchej, ale głęboko tw.rczej.

Crédit : Mathieu Chouinard, 2025.